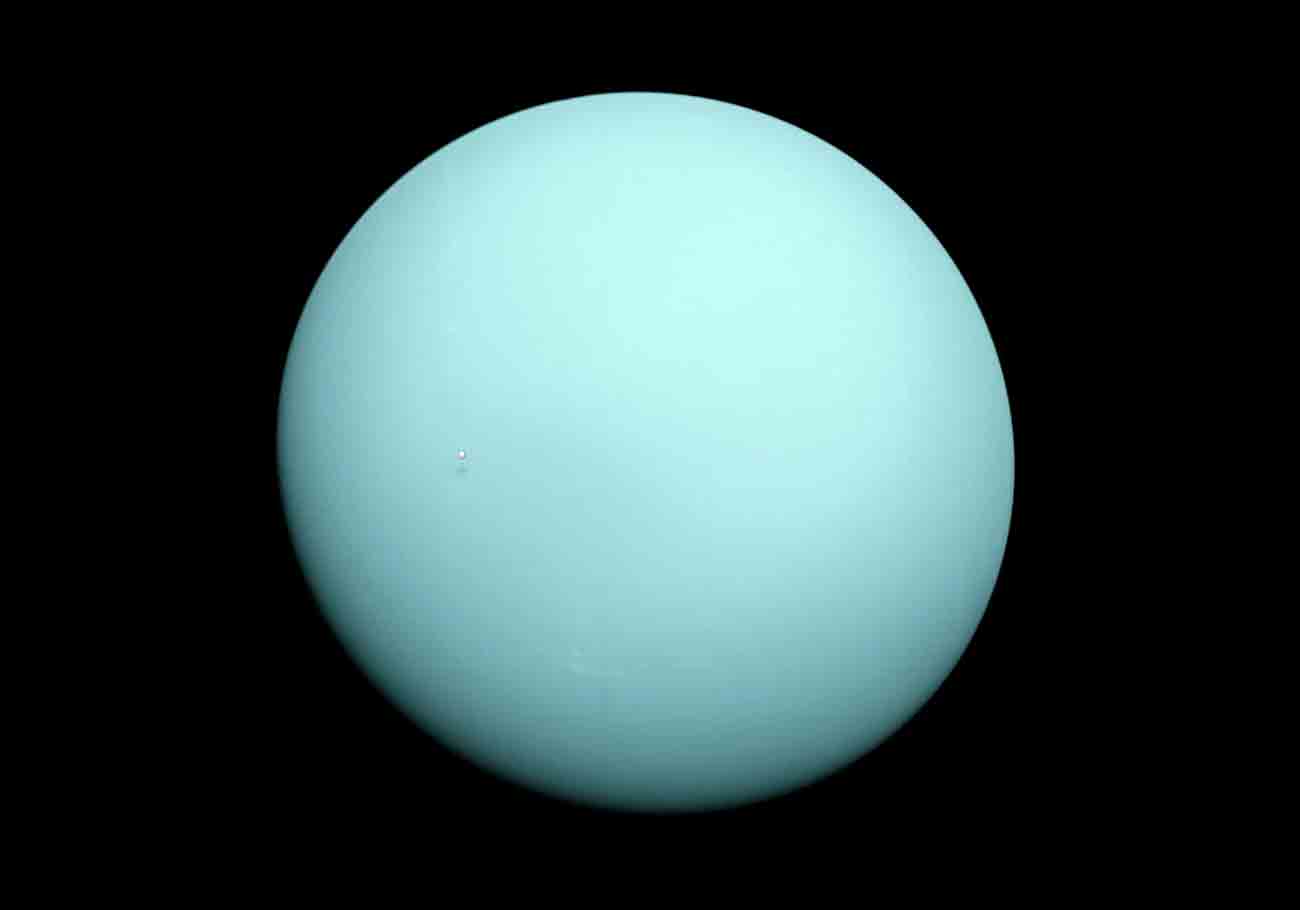

An article soon to be published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters has attributed Voyager 2 probe’s radiation observations to water molecules escaping from one of Uranus‘ moons. According to researchers, this could indicate the presence of an internal ocean and therefore, a chance for life.

+ Lockheed Martin Leaks Design of What Could Be Its 6th Generation Fighter

+ Video shows the destruction of armored vehicles by Ka-52 helicopter

+ Alessandra Negrini appears in underwear only in video: “Simply beautiful”

The researchers reanalyzed the radiation data from Voyager 2 and, in the new article accepted for publication, they state that the source is a band of energetic particles that were previously water vapor. “What’s interesting is that these particles were extremely confined near Uranus’ magnetic equator,” said the study’s lead author, Ian Cohen, from Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, in a statement.

Based on Voyager 2’s observations, it appears that the particles are confined to a band between Ariel and Miranda, the innermost pair of Uranus’s larger moons. Such concentration is inconsistent with the initial explanation for the particles, which claimed they originated from the tail of Uranus’s strangely tilted magnetosphere.

Saturn’s moon, Enceladus, releases water vapor from geysers linked to an internal ocean, and Europa, of Jupiter, likely does the same, though less frequently. Consequently, there’s nothing implausible about one of the Uranian moons, equally covered by a thick layer of ice, having a heat source inside that can maintain the internal ocean in liquid state.

Similarly, if Enceladus can release enough water molecules to supply a substantial portion of Saturn’s E ring, one of the two moons could certainly be responsible for these energized particles.

From liquid water to life is certainly a big step, but as recent evidence has shown, Enceladus has all the necessary ingredients. Moreover, it is likely that Ariel and Miranda are leaking similar resources.

It may be difficult for life to originate in the dark ocean of an icy moon. However, there’s a more disappointing explanation: that the particles are the result of the surface ice of one of the moons being sputtered. Cathode sputtering occurs when high-energy particles from sources like the solar wind hit the surface of an object without an atmosphere and knock off other particles.

Why the sputtering would only occur on one or both of Ariel and Miranda, and not on three similarly-sized moons, has not been explained, but Cohen admits that it is as plausible as the geyser hypothesis. “Right now, it’s about 50-50, whether it’s just one or the other,” Cohen added.

He admitted that this question likely won’t be resolved, nor which moon is responsible, using only the data collected by Voyager 2. The encounter was too brief, and the equipment used was too primitive to tell what the researchers need to know. One more reason why a mission to Uranus is moving up on NASA’s priority list.